Cultural Appropriation?

Parts 1 - 4 of 7

Part One

When the heart weeps for what it has lost, the spirit laughs for what it has found.

— West Africa

I have written about grief – indigenous ceremonies, the consequences of our American inability to grieve and the need to restore what Francis Weller calls an apprenticeship with sorrow:

I lead grief rituals at men’s conferences, and for twenty years my wife Maya and I led them in our early November Day of the Dead Ritual. So, we were bewildered when a friend challenged us: had we been engaging in “cultural appropriation” in referencing the Mexican holiday but not celebrating it in precisely the way Mexicans do, and of course, by not being Mexican ourselves?

Fair enough. So, intending to be as clear as possible about what we do and why (indeed, I define “radical ritual” as the clarification of intention), I plunged into the vast debate on this topic.

Susan Scafidi, in Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law, defines cultural appropriation as

Taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission…(including) unauthorized use of...dance, dress, music, language, folklore, cuisine, traditional medicine, religious symbols, etc.

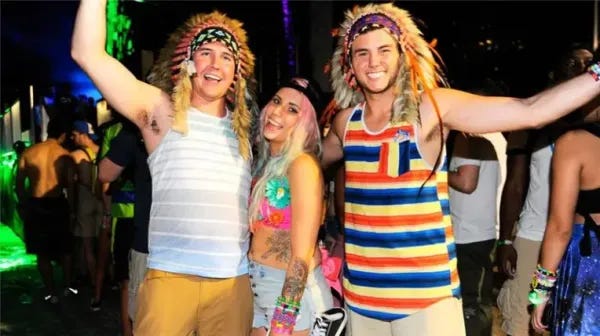

Cultural Appropriation occurs when members of a dominant culture use aesthetic forms or artifacts from other cultures – or profit from them – but show no respect for their deeper meaning. In its racist extreme, it can perpetuate old colonial messages that Third-World cultures are free for the taking.

“By dressing up as a fake Indian”, one Native American told white students, “…you are asserting your power over us...”

It is an aspect of white privilege, including the privilege to name sports teams “Indians”; the privilege to choose a Native American “mascot” for one’s school (nearly 2,000 American schools still do this); the privilege to name an oil drilling corporation “Apache”; the military’s privilege to name an attack helicopter (“Black Hawk”) after an indigenous leader who had resisted that same military; and the privilege of the CIA to co-opt the notion of “wokeness”.

Black feminist bell hooks wrote of “eating the Other”, the one-way consumption of cultures and the assertion of power and privilege. Chera Kee writes:

…this “cultural cannibalism” concerns power relations that grant white peoples the ability to enjoy the privilege of being able to borrow from other cultures without having to experience what it is actually like to be a member of another culture…to try on the culture of the Other without any real fear that one would truly become like the Other…to have all the pleasures associated with being the Other without any of the frustrations.

For more, see Chapter Ten of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence, or my essay A Vacation in Chaos.

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of cultural appropriation is imbalances of power. When people from privileged cultures or backgrounds attempt to dictate what is and isn’t cultural appropriation, they are reinforcing this imbalance that has continued to steal the voice from people of color throughout history. As far back as 1993, some 500 representatives from 40 different Native American tribes passed a “Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality.”

It’s complicated. Tamara Winfrey Harris writes:

A Japanese teen wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with the logo of a big American company is not the same as Madonna sporting a bindi as part of her latest reinvention. The difference is history and power. Colonization has made Western Anglo culture supreme...It is understood in its diversity and nuance as other cultures can only hope to be.

Very complicated. The African American community itself struggles with these questions. Is it cultural appropriation for an American Black person to wear a dashiki? Some Africans think so. Meanwhile, some New Zealand Māoris have accused a South African rugby team of appropriating their cultural traditions by performing an all-Black haka dance. Some Romani (whom we used to call “Gypsies”) people argue: “Your Tarot Card Practice is Romani Cultural Appropriation.” Contemporary Neo-Pagans argue about what they may be appropriating, to which John Halstead answers, “We’re all appropriating dead pagan cultures”.

It all comes down to permission, right? Well, it gets more complicated. Kenan Malik asks, what does it mean for knowledge or an object to “belong” to a culture? Who gives permission for someone from another culture to use that knowledge and those objects? And by whose authority are they permitted to announce themselves as gatekeepers?

After all, to suggest that it is “authentic” for blacks to wear locks, or for Native Americans to wear headdresses, but not for whites to do so, is itself to stereotype those cultures…The history of culture is the history of cultural appropriation... borrowing, stealing, transforming. Nor does preventing whites from wearing locks or practicing yoga challenge racism in any meaningful way. What the campaigns against cultural appropriation reveal is the disintegration of the meaning of “anti-racism”. Once it meant to struggle for equal treatment for all. Now it’s defining correct etiquette. The campaign against cultural appropriation is about policing manners rather than transforming society.

Rhyd Wildermuth adds:

Who owns dreadlocks – Black Americans or the other peoples who have also worn dreaded hair, including the Ngapa of India, the Cree, Aztec priests, the Poles, the ancient Greeks and the Massai?...often an apparent claim to exclusivity or ownership is historically inaccurate …Likewise, a long list of words “exclusive” to AAVE (African American Vernacular English) used to police cultural appropriation in online forums contains quite a few words developed earlier among other English-speaking peoples (including ain’t, y’all…claimed as exclusive property of AAVE but used much earlier in English Cockney and Australian slang).

Oddly enough, cultural appropriation originally referred to how marginalized people made use of dominant cultural forms for their own purposes. The spiritual song “Go Down Moses” appropriated the Jewish story of escape from Egypt to sing openly about their desire for freedom by using their masters’ sacred texts. But its current usage has three problems:

First of all, the concept is no longer rooted (if it ever previously was) in historical understanding of how cultures are formed…The second problem is that arguments about who should or shouldn’t be allowed to wear, eat, believe, worship, or practice things enforce notions of cultural, racial, and ethnic separatism that mirror nationalist and monotheist fears about miscegenation, cultural mixing, and foreign pollution. Third, despite attempting to fight imperialist colonial forms of oppression, the concept now reproduces a uniquely Western capitalist framework in which even sacred cultural forms – air, water, and other parts of the world previously exempt from economic logic – are subject to the logic of Neoliberal privatization and commodification.

Indeed, those who attempt to keep their own culture “pure” and free of borrowed elements may well fall into a cultural – or literal – fascism, as is developing among right-wing pagans in Eastern Europe, Russia and Britain.

In America, religion, empire and business have been intertwined since the beginning. As my book details, the disillusionment following World War Two and the Korean War eventually resulted in a longing for authentic spiritual traditions. By the 1960s, thousands were sampling Eastern or Native American religion. The New Age was born, and along with many legitimate teachers came the con-men, who appropriated for profit.

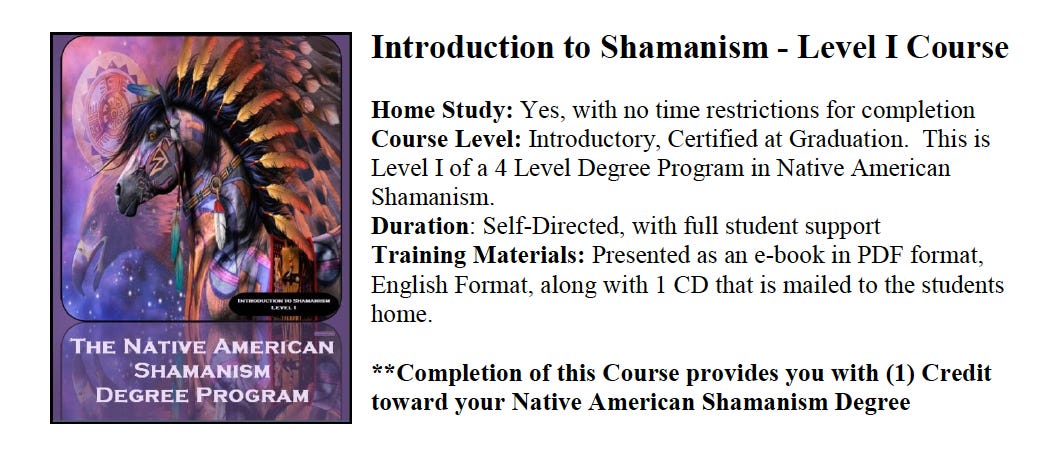

“Selling the Sacred: Get Your Master’s in Native American Shamanism?” The Native American journal Indian Country, complains,

New Agers in Indian country have made a popular culture of the sacred invisible, selling it to the highest bidder...the Divine Blessings Academy, which objectifies and quantifies spirituality as a product…offered a four-year degree, a master’s program, and post graduate degree in Native American Shamanism...The course catalogue offers courses in: The Hopi Prophecy Stone, Smudging and Basic Tools, Finding Your Power Animal, Reiki Using Native American Principles, Creating and Using Feather Fans, Native American Mantras and Prayers, receiving a Magikal name ...Graduation entitles the student to join the Native American Shamanism Society and to receive “a personalized full-color certificate.”

The cosmetic chain Sephora marketed a $42 ‘Starter Witch Kit’ that included a tarot deck, a crystal, white sage and perfumes until it faced a backlash campaign from real witches.

The shadow of American individualism is the willingness to immerse oneself in a large community of people who might give themselves (or their money) away. America is the home of the Big Con, from scandal-plagued televangelists to demagogue politicians to motivational speakers like James Arthur Ray, who appeared in the film The Secret. In 2009 he took advantage of this desire for authentic experience, charged participants $10,000 for a short retreat and led a faulty sweat lodge ceremony that resulted in three deaths. After completing his prison term, Ray, true to the con-men ideal, re-launched his self-help business, live on CNN.

Part Two

The alternative to cultural appropriation is cultural appreciation, or “cultural exchange”: learning about another culture with curiosity, respect and courtesy. We take the time to learn about a certain culture, interact with its members and perhaps receive a blessing to carry its wisdom forward. The operative word here is permission.

Universalist-Unitarians, known for sensitively using many cultural forms, have this poem on their website:

Our first task in approaching

Another people, another culture, another religion

Is to take off our shoes

For the place we are approaching is holy.

Else we find ourselves treading on another’s dream.

More serious still, we may forget...that God

Was there before our arrival.

It suggests questions that “borrowers” need to ask:

1 – How much do I know about this tradition; how do I respect it and not misrepresent it?

2 – Do I know the history of the people from whom I am borrowing?

3 – Is this borrowing distorting, watering down, or misinterpreting the tradition?

4 – Is the meaning changed?

5 – Is this overgeneralizing this culture?

6 – What is the motivation for cultural borrowing? What is being sought and why?

7 – How do the “owners” of the tradition feel about it being borrowed?

8 – If artifacts and/or rituals are being sold, who profits?

9 – Is this spiritually healthy for Unitarian Universalists?

10 – How can we acknowledge rather than exploit the contributions of all people?

As the frameworks of culture evolve, so does the definition of what constitutes appropriation. The context of how something is regarded, shared, explored or used may vary within different cultures and different time frames...there is no clear definition of what is and is not acceptable ...Context is everything.

She quotes three persons who’ve struggled with these questions. The first is anthropologist Sabina Magliocco:

… while on paper one can try to distinguish appropriation from exchange, in practice, it’s much more complicated...Think of cultural exchange as a crossroads. In folklore, the crossroads is a liminal place of magic, but it’s also a dangerous place, a place where death and destruction can happen. Crossroads deities are tricky (Eshu, Loki, Odin) and fierce (Hekate). Yet from that destruction and trickery, new life arises. It’s the same with cultural contact and exchange.

…the premise is that the two cultures entering into the exchange are on equal terms…Cultural material – narratives, verbal lore, music, material culture, foodways, magical techniques – are shared as part of the process…avoiding cultural appropriation is about respecting the feelings and rights of other cultures with which you co-exist. It’s about recognizing when there’s a history of power-over, exploitation, and cultural destruction, and being mindful of that…

Lupa Greenwolf describes her path:

…in the U.S. there is no established shamanic path, and so people who come from that culture (like me) have to choose either to try to shoehorn ourselves into an indigenous culture that we may not be welcome in let alone be trained in, or research cultures of our genetic ancestors and find that we are no more “culturally” German, or Slavic, or Russian than we are Cherokee or Dine’. Or we take a third road, which is to try to piece together some tradition that carries the same basic function as a shamanic practice in another culture, but which is informed by our own experiences...

...the biggest problem is when non-indigenous people take indigenous practices and claim to be indigenous themselves…because we get lumped in with those who outright lie about who they are. So you need to be honest and clear about where your practices come from and what inspired them…

I’ve had people tell me everything from “You shouldn’t use the word ‘shaman’” to “You shouldn’t use a drum with a real hide head” to “You shouldn’t work with hides and bones at all”, all because I’m a European mutt...I kept acquiescing to whoever criticized me, and then I realized that if I gave in to every criticism, I’d have no practice at all. So I carefully reviewed what my practice entailed, did my best to claim that which I created myself while also being honest about how other cultures’ practices inspired me…

Kenn Day adds another factor: American individualism:

… the term “post-tribal shamanism” differentiates between the teachings I received and those of tribal cultures. However, many people make the assumption that, if you are practicing ceremony with ancestor spirits, then you have taken your practice from a native tradition… The call to practice shamanism is found in every culture. It appears differently, yet it is still recognizable. The most important difference I see between the shamanism practiced in tribal cultures and what I teach is that the tribal practices are focused on supporting, healing and maintaining the most import unit of that culture: the tribe itself. Our situation is dramatically different, in that our most important unit is the individual...many traditional practices are simply not appropriate for use with individuals, just as what I do would not be appropriate for tribal people.

Americans are the tribe of those who have no tribe. What does it mean to not have countless ancestors whose bones enrich the soil we stand upon? Seeing appropriation from this perspective, we may realize that our lack of rootedness, our racism, our materialism, our contempt for our own children, our culture of celebrity, our desperate need to keep moving around and our willingness to ignore our genocidal violence are all related.

Part Three

When the iron bird flies and horses run on wheels, the Dharma will come to the land of the red faces. – Tibetan Prophecy

What about those emissaries from Tibet and other cultures who choose to come here to spread their wisdom? All those Yogis, Lamas, Sufis, Zen masters, ayahuasceros and gurus (a word now used so commonly that most people probably don’t realize its Hindu origin)?

All those who came to teach Tai Chi, Aikido, Judo, Kung Fu, Jujitso, acupuncture, herbalism, Qi Gung, I Ching, Feng Shui, Karate, Tae Kwon Do, Capoeira, Vodoun, Santeria, Candomble, bagpipe, gamelan, didgeridoo, tango, hora, samba, klezmer, nigun, rebetika, kirtan, raga, sitar, koto, oud, ney, kalimba, belly dance, hula, slack key, ho’oponopono, Cuban Jazz, Balkan choral chant, Flamenco, West African dance, drum and divination, Irish fiddle, Tuvan throat singing, Roma violin, Aztec dance, Oaxacan weaving, Greek dance, Andean pan pipe? All those exotic crafts and jewelry? All that food?

Is America really a “melting pot” or is it more of a mosaic? And in the other direction: what about all that enthusiasm for American Jazz in France, or Blues societies in Japan? And, yes, Americans teaching meditation in India?

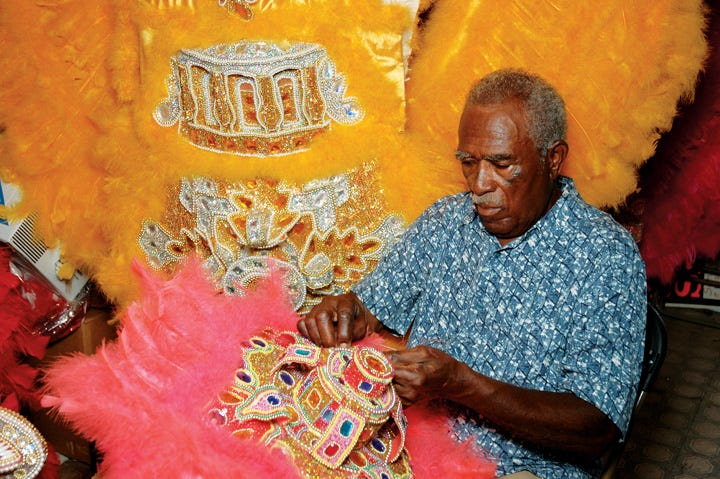

How about the curious case of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians, African Americans who have marched and danced in astonishingly creative yet seemingly caricature “Indian” outfits since the 1880s?

Isn’t this cultural appropriation, no different from Indian-named sports mascots? Or from all-white clubs appropriating foreign (like the “Shriners”, the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine), or native styles (such as the “Improved Order of Red Men”, which claimed to have a million members in the 1930s and a women’s auxiliary, the “Degree of Pocahontas”)?

Humor may be our best way out of this. In 2002 a mixed-race basketball team at a Colorado college called themselves the Fightin’ Whites.

The Mardi Gras Indians have given considerable thought to their masking. They named themselves after “Indians” in appreciation for their historic willingness to assist, protect and intermarry with escaped slaves. Ronald Lewis, former Council Chief of the Choctaw Hunters and curator of the “House of Dance and Feathers” museum, wrote:

Masking like Native Americans created an identity of strength. Native Americans under all the pressure and duress would not concede. They were almost driven into extinction, and the same kind of feeling came out of slavery, “You’re not going to give us a place here in society, we’ll create our own.” In masking, they paid homage to the Native Americans by using their identity and making a social statement that despite the odds, they’re not going to stop.

The difference between this tradition and those condescending sports mascots returns us to questions of power and privilege – billionaire owners of sports teams and their man Trumpus vs. disenfranchised ethnic minorities.

It’s complicated. Allison “Tootie” Montana, the most famous of the Mardi Gras maskers, invited to New York City to view an exhibition of ancient African art, exclaimed that it looked exactly like the costumes his people had been designing for years, that Africans had been copying him!

Perhaps Montana, who had never been exposed to the art of his ancestors across the water, had intuited these art forms directly from the collective unconscious.

Back to the Tibetans, etc: Aren’t these teachers asking for Americans to appropriate/appreciate their spiritual traditions? And what about other teachers who have come here because they know that if Americans don’t popularize those ways, then – as Martin Prechtel’s teacher told him – those traditions would disappear in their indigenous lands? Or, like the Kogi people of Colombia, who teach that if modern people don’t learn their ways, the whole world might not survive? As one wise friend says, “We must live among them in order to save them!”

Part Four

So, were Maya and I being culturally appropriate all these years? Along with permission, we need to address calling, authenticity and community.

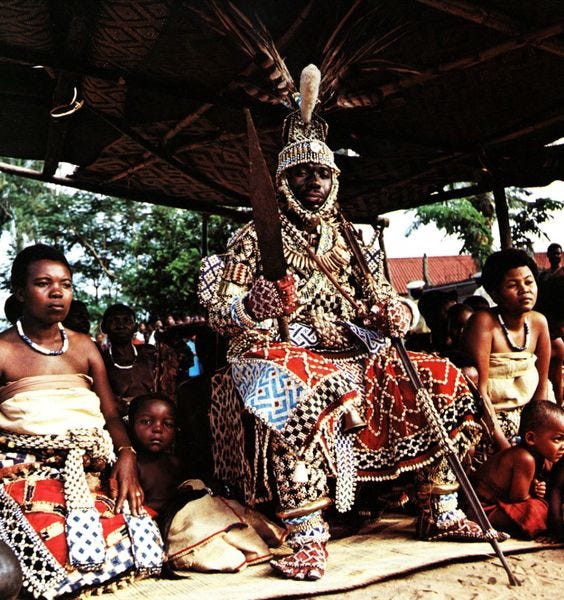

After participating in several Dagara (West African) grief rituals led by Malidoma Somé at men’s conferences in the 1990s and at other events with his wife Sobonfu, I felt called to this work. Maya speaks of her calling here. Malidoma blessed us and told us to take the work into our communities.

Next comes the question of authenticity, the issue over which our friend was challenging us. Clearly, to call our event a “Day of the Dead Ritual” was not strictly accurate. So we must speak of the fourth term, community.

Malidoma, whose elders had sent him to the West, and whose name means “”He who makes friends with the strangers,” emphasized that there is no community without ritual and no ritual without community. Where is genuine community in America, people who live close by, know each other and are also willing to engage in radical ritual? It’s a conundrum that, if followed literally, leads to indecisiveness. Although traditional Dagara funerals require the participation of the entire community and take 72 hours to complete, Malidoma said that shouldn’t inhibit our attempts to bring the work into the world. It was too important to split hairs over.

Dia de Los Muertos, intimately associated with Mexican, syncretistic Catholicism, lasts for several days. The living invite the dead to visit their homes with colorful displays and their favorite foods, but the people spend the central night of the festival at gravesites. And it is a festival! Grieving is common but certainly not the sole emotion. The people party with their dead as only Mexicans can.

There is no way to make a short event in a public hall for a group of non-Catholics, most of whom have never met each other, into an authentic Dia de Los Muertos.

So first, we remember (sadly) that there is no community in the indigenous sense. The best we can do is to invite likeminded people to gather in brief periods of what Michael Meade calls “sudden community.” At our rituals, we encouraged everyone to act (and speak) as if we all were members of a tribe who’d known each other all our lives. We made sudden community for a few hours.

Many other cultures set aside an annual period for the dead to return, with terminology that translates as their own Days of the Dead. And they understand that certain liminal times are most appropriate. Eastern cultures that use lunar calendars have these rituals a half year from the Lunar New Year, often on the first full moon in August. This is what the Mexicas (as the Aztecs called themselves) did. Their holiday lasted for twenty days, beginning on approximately August 8th with Micailhuitontli (Small Feast of the Dead), to honor deceased children, and ending with Huey Micailhuitl (Great Feast of the Dead), remembering those who died as adults.

It’s complicated. Once the padres acknowledged that they couldn’t extinguish the ancient rites, they forced the Mexicas to change the dates of their festival from August to early November, the time of the Catholic festivals of All Saint’s and All Soul’s. But these festivals had been created back in the 10th and 11th centuries, when the Church finally decided that it couldn’t wipe out the immensely old Celtic festival of the dead.

Samhaim, as the Irish called it, had always fallen on that liminal point in the solar calendar precisely between fall equinox and winter solstice, when the light half of the year switched to the dark half and the veil between the worlds was the thinnest, when the boundaries between the seen and unseen worlds thinned, and the spirits of the dead walked briefly among the living. The secular holiday of Halloween arose from it when the Irish came to America. To contemporary Neo-Pagans, however, these are still times for loving remembrance. They are also liminal, sacred times, when great things are possible.

And they are dangerous times, since some spirits arrive hungry for more than physical food. Tribal people from Bali to Guatemala agree that there is a reciprocal relationship between the worlds. What is damaged in one world can be repaired by the beings in the other. Such cultures affirm that many of our problems arise because we have not allowed the spirits of the dead to move completely to their final homes – by not grieving them fully. Hence the Catholic concept of Purgatory.

Maya and I had also been attending the annual Spiral Dance, San Francisco’s “Witch’s New Year”. Now in its 47th year, it is both a time for grieving the dead and a party that welcomes both the darkness and the imagination necessary to move forward.

We also joined in the Day of the Dead Procession. Latinos in the Mission District introduced this tradition in the 1970s, but it soon grew into a major San Francisco event, with thousands of participants, mostly young white artists and college students. Some criticize it as merely an excuse for a public party with its drumming, samba dancers and LGBTQ themes. But each year the procession passes many poignant front-porch shrines and concludes at a park where people have created dozens of illuminated ofrendas, or shrines to their dead, and celebration turns to mourning. At each shrine, the message is, “Look, I have lost someone. See me. Come weep with me.” Appropriation? I don’t think so.

In Los Angeles (previously known to the native Chumash as Yaanga, or “Poison Oak Place”), the Hollywood Forever Cemetery hosts an annual Dia De Los Muertos celebration, with dozens of beautiful and thoughtful ofrendas. But this is L.A., where everything invites commercialization. In 2017 Netflix built five of these shrines to honor fictional characters who’d died that year. Appropriation? I think so.

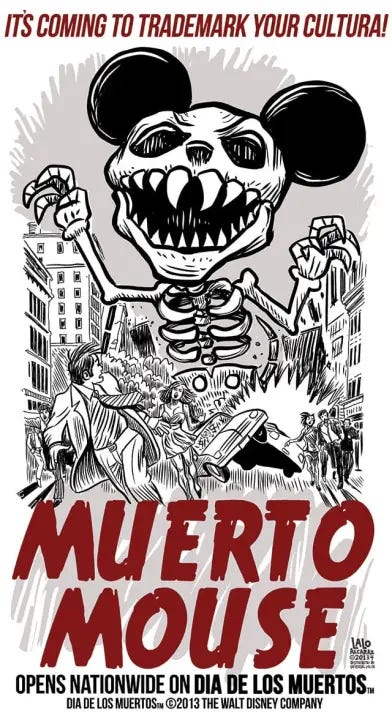

You can’t make this stuff up. In 2013, the Disney Corporation attempted to trademark the phrases “Día de los Muertos” and “Day of the Dead”. The Latino community responded with a petition featuring a ferocious poster advertising “Muerto Mouse” and quickly gathered over 20,000 signatures.

Disney, to its credit, backed down and even hired the poster’s creator Lalo Alcaraz as a creative consultant on their film Coco, which with his help turned out to be culturally accurate.

Celtic New Year and Day of the Dead have far more in common than differences, and both are completely consistent with the Dagara ritual imagination. How, I asked Malidoma, do people acknowledge seasonal transitions in an equatorial country such as his (Burkina Faso), where there is no difference between the light and dark halves of the year? His answer: the Dagara observe daily transitional times, dawn and dusk.

Another commonality: In Martín Prechtel’s teachings from Guatemala, the ancestors require two basic things of us: beauty and tears. The fullness of our grief, expressed in colorful, poetic, communal celebrations, feeds the dead when they visit, so that when they return to the other world, they can help those remaining in this one. Feeding them with our grief, we may drop some of the emotional load we all carry simply by living in these times. Ghosts can become ancestors.

But they need our help to complete their transitions. Without enough people weeping for it, say the Tzutujil Maya, a soul turns back. Taking up residence in the body of a youth, it may ruin their life through violence and alcoholism until the community completes the appropriate rites. This is the deeper teaching: when we starve the spirits by not dying to our false selves and embodying our authentic selves, the spirits take literal death as a substitute.

We witnessed a Balinese cremation ritual and saw more cross-cultural parallels.

It made perfect sense to respectfully incorporate some of these patterns into our rituals. Recalling Lupa Greenwolf’s words:

So I very carefully reviewed what my practice entailed, did my best to claim that which I created myself while also being honest about how other cultures’ practices inspired me…

David Chethlahe Palladin had strong opinions on this issue. He was a medicine man and one of the best-known Native American artists of his generation (read about his extraordinary life story here). A painter, he mixed cross-cultural mythic images with traditional Navaho themes and wrote:

There may be times in our personal evolution when we become aware of archetypal themes that exist within the universal consciousness, and we draw upon them, regardless of their cultural or tribal origin.

Pagan thinking appreciates diversity and encourages us to imagine. Myth is truth precisely because it refuses to reduce reality to one single perspective. Maya and I came to entertain the possibility that if there is such a thing as truth, it resides in many places. And we felt called to appreciate the wisdom from many indigenous cultures, rather than to follow one path exclusively.

Besides, the times are too painful and the need is too strong to reject anything authentic. We have proceeded on the assumption that we need all the help we can get. Even Malidoma would address his ancestors by acknowledging that so much wisdom had already been lost, that he was clumsily trying his best and hoping that the spirits would listen.

Whenever we encounter people of serious intention who are also attempting to revive or create a truly indigenous imagination on this land, they intuitively understand the basic principles of ritual. Radical ritual, that is:

1 – Every American carries immense loads of unexpressed grief and unfinished business that can sabotage our relationships and future goals.

2 – Beings on the other side of the veil call to us continually. The way to approach them is through ritual. This often involves creating beautiful shrines.

3 – Radical ritual implies creating a strong container, clarifying intentions, inviting the spirits to enter, and not predicting the outcome. It is not liturgical but emotional.

4 – Radical ritual is always communal work.

5 – The purpose of radical ritual is to restore balance and clarify intention.

6 – When ritual involves the body, the soul (and the ancestors) take notice. Drumming encourages participants to dance their grief. All emotions are welcome.

7 – Ritual involves sacrifice. We attempt to release whatever holds us back or keeps us stuck in unproductive relationships. The ancestors are eager for signs of our sincerity. What appears toxic to us, that which we wish to sacrifice, becomes food to them, and they gladly feast upon our tears as well as upon our expressions of beauty.

When we meet people with similar interests from other parts of the country or Europe, either we find that they have already intuited the same basic principles or are quite willing to learn them.

But what about other ritualists who charge exorbitant rates? Are we, who never refused admission to our events to anyone for lack of funds, to judge them? Well, this is America after all. Perhaps many of us simply don’t value experiences if they aren’t expensive. Indeed, as my ceramicist friend Larry Robinson says, “When my pots don’t sell, I raise the price.”

In summary, after researching this dispute, we concluded that our work and our terminology – a Day of the Dead Grief Ritual – fell squarely on the side of appreciation. May the ancestors bless our endeavors.

Parts 5-7 will follow soon.